On a fine day, Dr. A had three patients come in:

- A 1.5 years old, medium sized, Indie male dog, weighing 14kg for elective Orchidectomy, with history of bilous vomit once in 2-3 weeks.

- An 8-year-old intact male Labrador, weighing 42kg, with history of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia and stranguria.

- A 9-year-old intact male pug, weighing 7.2kg, with history of diabetes, blood glucose levels well under control for over a year, for Orchidectomy as clients wish to move with him to USA.

Even though all three require the same surgical procedure, Dr. A needs your help with preanesthesia check (PAC). Would it work if all patients undergo same preoperative blood tests? Fasted for 4-6 hours? Anesthetized with the usual protocol for elective surgeries? Monitored with routine ECG and pulse oximetry during surgery? Have the same postoperative care? I wish, that was the case.

Since their comorbidities immensely vary, the conversation you have with each client regarding anesthesia risk would be completely different.

How to perform a PAC?

Physical exam is an integral part of PAC. It is something which we are taught in the initial years of Veterinary College- examine your patient from nose to tail. But a few years of experience later, it is taken casually or for granted- the patients coming in for an elective surgery must be fit. A physical exam for PAC must include:

- Checking temperature

- Mentation of the patient

- Color and consistency of mucus membranes

- Dental hygiene

- Size of lymph nodes

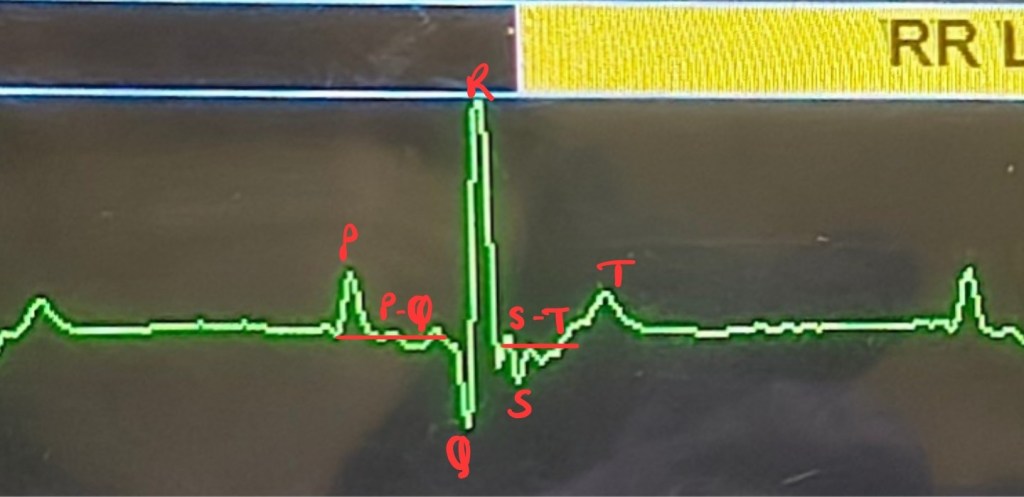

- Auscultation of chest for lung sounds, heart sounds and simultaneously pulse quality

- Abdominal palpation for each organ, checking for enlargement or pain.

- Checking ears, skin and limbs for ectoparasites and infection, specially at the site of incision.

- Asking the client about patient’s diet, if stools and urine are normal, vaccine and deworming status, recent medical history and current medicines he/she is on, and any known allergy.

Blood samples for complete blood count (CBC) and biochemical values to evaluate renal and liver functions (RFT and LFT). CBC gives information about hemoglobin and RBC count which represent oxygen carrying capacity, leucocyte count tells us about an infection, if any, and normal platelet count is essential for forming blood clots to stop intraoperative bleeding. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine and electrolytes are the functional values of kidneys while total proteins, albumin and globulin are functional values of liver. SGPT/ALT is an inflammatory indicator of liver. These two organs play a vital role during anesthesia to metabolize and eliminate the drugs. Blood glucose is included in PAC as surgery is a physiologically stressful event for the body, causing metabolic imbalance and alters glucose levels. Few countries mandate routine urine test in PAC to assess post renal dysfunction. If an abnormality is detected in the blood tests, it warrants for further investigation. Geriatric patients, most dog breeds over 8 years of age and cats over 10 years of age3, should be advised for a cardiac examination, as heart diseases are common at that age. Auscultate every patient, focusing to listen for a cardiac murmur. Assess heart size on chest radiograph. If an abnormal heart sound is diagnosed, opt electrocardiogram (ECG) for arrhythmias and/or 2D Echocardiography for cardiac function.

No matter how advanced our diagnostic technology is, it cannot and should not replace a patient’s physical exam performed by a doctor.

Veterinarians should not solely rely upon diagnostic tests to infer that the patient can undergo anesthesia. A thorough physical exam gives more than 75% of the information you need to determine if the patient is fit for anesthesia. Diagnostic tests are just supportive evidence to your findings. A study found that, if no significant issues were identified in physical exam and patient’s history, the blood tests usually do not reveal any new information that would change the anesthesia plan1. Same study also documented change of anesthesia plan in 8% of their subjects with abnormalities in hematologic and biochemical levels. In human medicine, clear framework exists recommending specific blood tests based on information obtained from the patient’s medical record, clinical examination, ASA status, patient interview and nature of procedure. Such clear recommendations do not exist in veterinary medicine currently. The hematological and biochemical values tested are based on historical practice and clinical experience rather than evidence-based medicine3.

Should I not conduct diagnostics?

Although a clinician’s ability to declare patient’s fitness for surgery is of prime importance, it does not render diagnostic tests pointless. There are many instances where abnormal blood test reports demanded changes in anesthesia protocol, subclinical diseases and chronic conditions were unexpectedly diagnosed during PAC. At times, the surgery may need to be postponed or canceled due to the underlying condition. There are increasing incidences of clients blaming doctors when things go wrong in relation to anesthesia, even when in many cases this may be completely unjustified. This is why many clinicians conduct blood tests as it acts as a tangible proof that the patient is fit for anesthesia1.

PAC is to acknowledge preanesthesia risks, to identify intraoperative priorities and to advise clients about expected complications prior to anesthesia. Anesthetic drugs cause cardiopulmonary depression and presence of pre-existing pathology is likely to predispose to greater anesthetic-induced physiologic disturbance. Compromise of major body systems will make the patients more prone to side effects of anesthesia5. Preoperative assessment of anesthetic risk is a valuable exercise to minimize and gauge complications and optimize anesthetic safety, and consequently good surgical outcome1.

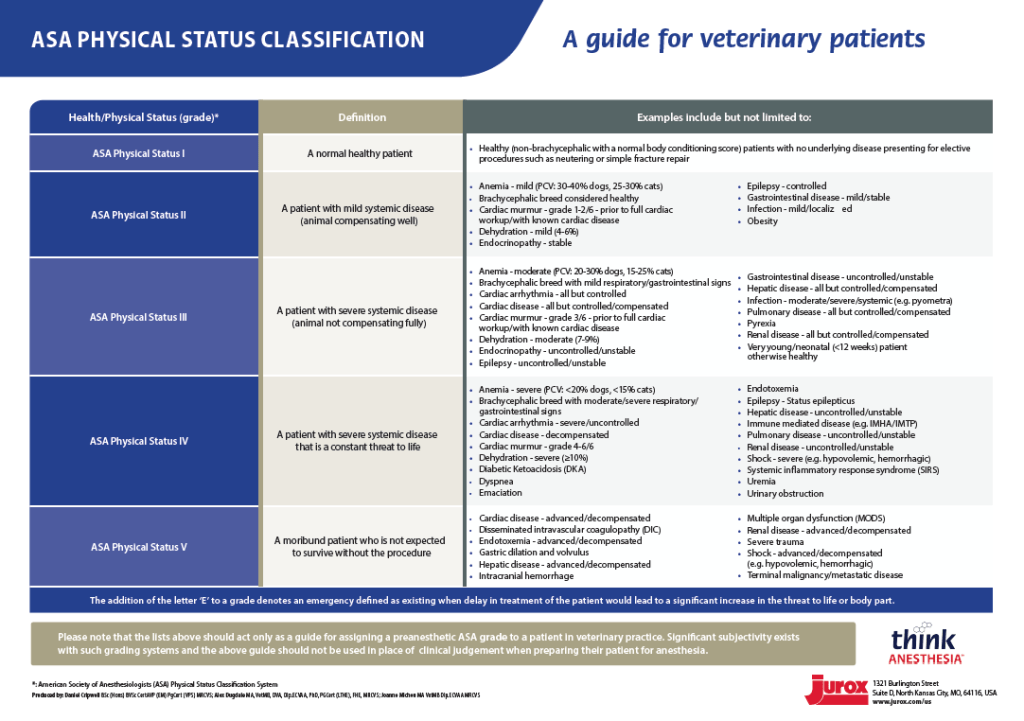

It is incomprehensible to clients when doctors use medical jargon to explain anesthesia risk, instead it is easier for them to understand it in terms of scale or numbers. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) in 1941 devised a system of classifying patients based on individual physical status and comorbidities which is used to predict anesthesia risks, complications and anesthesia-related death. It is called the ASA physical status (ASA PS) classification4. There are six classes in the latest ASA PS classification with E for Emergency status- delay in treatment/surgery would significantly increase the threat to life or body part. The ASA PS is known for its simplicity, each class includes various examples of diseases, disorder and abnormalities which hamper normal functioning of the body, known as the functional status. E.g. Anemia, asthma, renal diseases etc6.

Veterinary counterparts use only five classes, (I, II, III. IV and V) of ASA PS and E status, during PAC.

ASA PS I: A normal healthy patient.

ASA PS II: Patient with mild systemic disease.

ASA PS III: Patient with severe systemic disease.

ASA PS IV: Patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life.

ASA PS V: Moribund patient who may not survive without the surgery.

In human medicine, ASA class VI is assigned to brain-dead patients who are organ donors.

There can be subjective debates for a particular patient where one doctor can classify him/her as ASA PS III, while another can classify the same patient as ASA PS IV. To minimize such errors, examples of functional status are provided along with the classification4. This is the one I prefer to use7:

ASA PS not only helps to evaluate patients, but it also tells the clinician/anesthetist as to what precautions to take before anesthesia, helps with drug selection, parameters to monitor, if the patient needs additional monitoring or diagnostic tests before, during or after surgery, or if the surgery should be postponed or canceled. Patients with ASA PS III-V are at a higher risk of anesthesia-related death than those of ASA PS I-II. Dogs with ASA PS ≥III are at risk of anesthesia-related mortality up to 24hr after anesthesia, and that of cats with ASA PS ≥III for up to 72hr after anesthesia. Hence, more attention should be given during their recovery. Due to the impaired organ function, the patient cannot tolerate many anesthetic drugs, as the body is unable to compensate for the pre-existing dysfunction2,5.

Since there is no standard ASA PS classification available for veterinary use, you can form your own ASA PS classification for your practice. Begin by classifying routine OPD patients, imagining them as surgery patients. Whenever needed, this chart can be modified as per your experience and latest studies. Evaluating patients with physical examination, diagnostic reports and assigning ASA PS status will eventually be a part of your routine and will enhance your ability to correlate diagnostic reports with clinical examination, and find errors, if any. Make a checklist of physical exam parameters, questions to ask the client and go through it for every patient during PAC. In a few weeks, it will be easy for you to conduct PAC without refering the checklist.

You can refer the above chart and form ASA PS classifications for small animals, exotic animals, ruminants, equine practice and wildlife, as per your practice. Each ASA PS classification would differ as clinical presentation for each species varies a lot.

Spend few minutes more with every patient and examine them thoroughly (go through the PAC checklist), interpret and correlate diagnostic reports, classify your patients and explain the anesthesia risk accordingly. That would help you increase patient safety and build client confidence.

You can begin by helping Dr. A plan the three procedures. How would you classify the patients based on their clinical history alone? What diagnostic tests would you recommend for each patient? What are the expected complications during anesthesia? What would be your preanesthesia fasting instruction to each patient? How will you explain anesthesia risk to the respective client?

Comment your opinion below or email it to dr.sahilmehta@outlook.com

PS. There are no wrong answers.

Feel free to ask your doubts in the comment section/email. Connect with me on LinkedIn and Instagram. Subscribe to the AnesWise newsletter for future content notifications. Kindly leave a feedback as it helps improve the blog.

Edited by Prajakta Alase

Citations:

- Brodbelt, D.C., Flaherty, D. and Pettifer, G.R., 2015. Anesthetic risk and informed consent. Veterinary anesthesia and analgesia: the fifth edition of Lumb and Jones, pp.11-22.

- Brodbelt, D.C., Pfeiffer, D.U., Young, L.E. and Wood, J.L.N., 2007. Risk factors for anaesthetic-related death in cats: results from the confidential enquiry into perioperative small animal fatalities (CEPSAF). British journal of anaesthesia, 99(5), pp.617-623.

- del Mar Díaz, M., Kaartinen, J. and Allison, A., 2021. Preanaesthetic blood tests in cats and dogs older than 8 years: anaesthetists’ prediction and peri-anaesthetic changes. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 48(6), pp.854-860.

- Mayhew, D., Mendonca, V. and Murthy, B.V.S., 2019. A review of ASA physical status–historical perspectives and modern developments. Anaesthesia, 74(3), pp.373-379.

- Portier, K. and Ida, K.K., 2018. The ASA physical status classification: what is the evidence for recommending its use in veterinary anesthesia?—A systematic review. Frontiers in veterinary science, 5, p.204.

- https://www.asahq.org/standards-and-practice-parameters/statement-on-asa-physical-status-classification-system

- https://www.thinkanesthesia.education/sites/default/files/2021-03/US%20-%20ASA%20physical%20Status%20Classification%20Chart%20-%20%20V2.pdf

Leave a comment