Doctor: We have scheduled Tuffy’s surgery on Tuesday morning 9:00 and he has to come fasting for five hours.

Client: That will be very early in the morning. Is there any other option?

D: You can feed him late in the night. But later no food and no water.

C: That can be worked out. See you on Tuesday!

This is the conversation we have quite often with our clients. But do the fasting instructions seem vague to you? Is the recommended fasting period of five hours and the client-convenient overnight fast going to affect patient safety? Let us dig deeper into an Anesthetist’s favorite rule- NO FAST, NO SURGERY!

Is fasting a necessity?

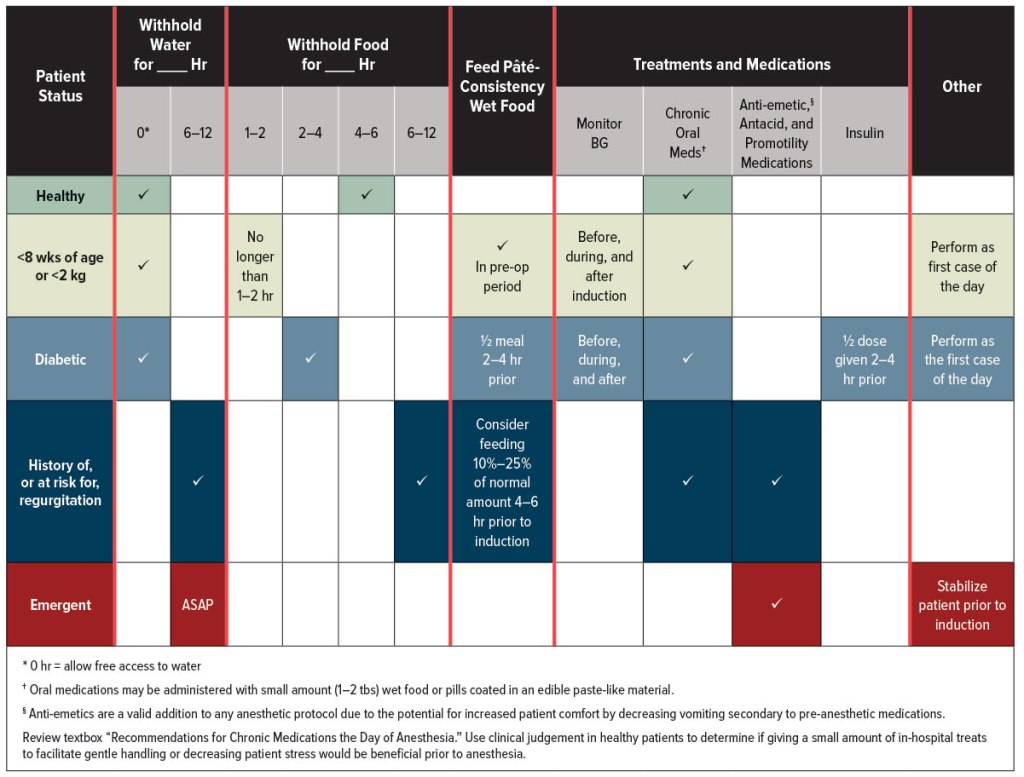

Many clients perceive preanesthesia fasting as a torture to their pets. Most clinics and hospitals schedule surgeries at 9:00 in the morning, whereas most pets break their fast at around 7:00 or earlier. Plight of clients is understandable. What are we achieving from this preanesthesia fasting recommendation? It is to reduce the volume of gastric contents (stomach acid ± food) during surgery and prevent untoward events of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and consequently, regurgitation and aspiration pneumonia. There is a need of solid evidence to change the concept of overnight fasting in Veterinary practice.

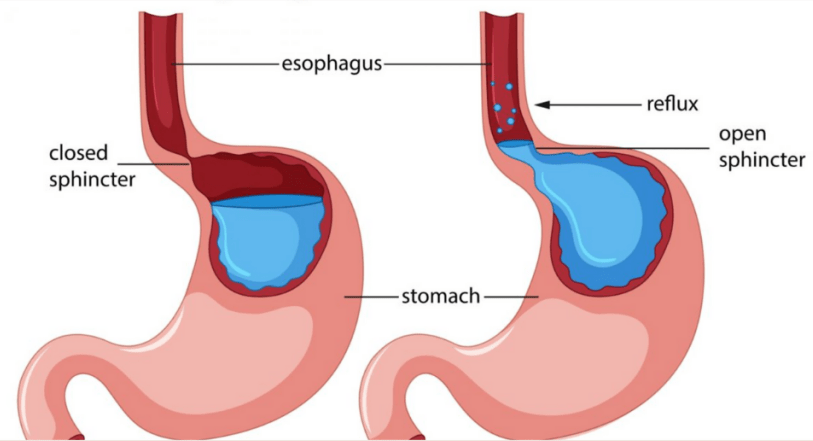

GER is a condition where gastric contents passively enter the oesophagus. Lower oesophageal sphincter (LES) is a valve between the oesophagus and stomach. Its function is to protect the oesophagus from stomach contents. Under general anesthesia, LES relaxes and allows gastric contents into the oesophagus. Since oesophagus lacks the healing serosal layer, the inflammation caused by the acidic stomach contents is challenging for the body to repair.

Dr. Ioannis Savvas estimates that GER occurs in 50-60% of dog patients under general anesthesia. However, exact number could not be determined as the stomach contents remain in oesophagus and asymptomatic patients go unnoticed by the clinician. These patients seldom develop oesophagitis, which manifests slowly over two to three weeks after the anesthetic episode. Symptoms of GER, when mild, are non-specific viz. dysphagia, coughing and nausea. Severe oesophagitis can lead to death or warrant euthanasia.

Despite a protective mechanism in place, why does GER happen in such large number of patients? Barrier pressure plays a vital role in preventing GER. It is the difference between the LES and the pressure in the stomach.

PBr= PLES– PIG

PBr: Barrier pressure, PLES: LES pressure, PIG: Intragastric pressure

Under general anesthesia, LES pressure is lowered, allowing intragastric pressure to push the stomach contents into the oesophagus. Handling abdominal organs increases the intragastric pressure, leading to GER. Simply moving the patient from preparation room to OR increases intragastric pressure.

Regurgitation is when the gastric contents from oesophagus move cranially into the pharynx and mouth. It is seen when the head and neck of patient is positioned lower than the level of its thorax, and the gastric contents gravitate from the oesophagus to the mouth. It is seen in <1% of dogs under general anesthesia.

Aspiration pneumonia is the worst outcome of a regurgitation episode where gastric contents enter into the trachea. Clinical symptoms depend on the volume of aspirate. Small particles of food block airway causing bronchospasm, coughing and wheezing. Large aspirates disrupt the airway epithelium and pulmonary surfactant function leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Prognosis of these patients depends on volume of aspirate, prompt diagnosis and aggressive treatment.

Can GER be prevented?

This is where fasting comes into picture. Risk of GER is highly dependent on the duration of fasting. The concept of overnight fast was borrowed from the human surgery rules into the veterinary field. It is found that, fasting for 4-6 hours in healthy adult dogs and cats reduces the incidence of GER. American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) recommends feeding half the amount of resting energy requirement (RER) of canned food or wet food (pH 4-5) before fasting the surgery patient. A study from 2009, using these parameters, found that the gastric volume was not significantly different and the stomach pH was higher, thus reducing the incidence of GER. Avoid feeding dry kibbles and diets with high protein and fat content, as it delays gastric emptying. If the patient is not compliant with sudden change of food or is a picky eater, homemade soft consistency food can be fed as an alternative.

Metoclopramide and Maropitant are known to increase LES pressure. While these are potent antiemetics in non-anesthetized patients, during surgery with the use of multiple drugs which have opposing effect on LES, their efficacy is debatable. Studies using antacids as premedication show no clear evidence that they help prevent GER. However, Metoclopramide and Maropitant do prevent the postoperative incidence of vomiting.

Cons of overnight fasting

Overnight/ prolonged fasting decreases gastric pH to as low as 2 or even 1! Under general anesthesia, the lowered pH increases the risk of GER and a small volume of such acidic content when enters into the oesophagus, and remains there for 30-60 minutes will lead to irreparable oesophagitis. Prolonged fasting is also not advised as the dysmotility and dilation prevents complete emptying of oesophageal contents and increased incidence of GER.

The regular IV fluids administered during surgery do not fulfill the daily energy, protein and other nutritional requirements of the patient. Thus, IV fluids should not be considered as a substitute for food on the day of surgery. It is essential that clients follow the required fasting duration for their pets, which will ensure patient’s safety during anesthesia.

Diabetic patients

Elective surgeries for diabetic patients need to be planned diligently. Diabetic dogs and cats eat food and drink water in excessive amounts and more frequently than non-diabetic patients. Clients would be reluctant to fast them for 4-6 hours as they are used to feeding their pets frequently. AAHA recommends fasting for 2-4 hours only for diabetic patients after feeding them half the amount of their prescription diet and not to withhold water. Patient’s insulin should be administered 2-4 hours prior to surgery with only half the regular dose. This prevents severe hyperglycemia during surgery. Patients with diabetes mellitus should be scheduled for surgery early in the morning. Check their blood glucose level before the procedure and every 30 minutes intraoperatively.

Risk factors for GER:

- Drugs like Atropine, Acepromazine, Propofol and Full µ-agonist opioids lower LES pressure

- Excessive handling of abdominal organs increases intra-abdominal pressure

- Frequent change of recumbency or limb position, mostly seen in orthopedic surgeries, causes increase intragastric pressure

- Deep chested patients positioned in sternal recumbency/ prone position on metal operating table causes distortion of diaphragm, as the weight of thorax sinks vertically downwards to the table and increases pressure on the diaphragm to displace it cranially

- Overweight patients have greater distortion of abdominal and thoracic organs in ventrodorsal recumbency/ supine position, increasing the intragastric pressure. It is commonly seen in (but not limited to) large to giant breed dogs weighing more than 40kg.

- Pregnant dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy in their second half of gestation exhibit GER, more than its incidence in non-pregnant dogs, due to increased abdominal volume.

Owing to the studies mentioned above, the traditional “nil per os after midnight” prior to anesthesia for healthy adult dogs and cats for elective procedures, should be reconsidered and shorter fasting recommendations be put in place for safer surgical outcomes.

Edited by Prajakta Alase

Citations:

Adams, J.G., Figueiredo, J.P. and Graves, T.K., 2015. Physiology, pathophysiology, and anesthetic management of patients with gastrointestinal and endocrine disease. Veterinary anesthesia and analgesia: the fifth edition of Lumb and Jones, pp.639-677.

Anagnostou, T.L., Savvas, I., Kazakos, G.M., Ververidis, H.N., Psalla, D., Kostakis, C., Skepastianos, P. and Raptopoulos, D., 2015. The effect of the stage of the ovarian cycle (anoestrus or dioestrus) and of pregnancy on the incidence of gastro-oesophageal reflux in dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 42(5), pp.502-511.

Anagnostou, T.L., Kazakos, G.M., Savvas, I., Kostakis, C. and Papadopoulou, P., 2017. Gastro-oesophageal reflux in large-sized, deep-chested versus small-sized, barrel-chested dogs undergoing spinal surgery in sternal recumbency. Veterinary anaesthesia and analgesia, 44(1), pp.35-41.

Lamata, C., Loughton, V., Jones, M., Alibhai, H., Armitage-Chan, E., Walsh, K. and Brodbelt, D., 2012. The risk of passive regurgitation during general anaesthesia in a population of referred dogs in the UK. Veterinary anaesthesia and analgesia, 39(3), pp.266-274.

Pratschke, K.M., Bellenger, C.R., McAllister, H. and Campion, D., 2001. Barrier pressure at the gastroesophageal junction in anesthetized dogs. American journal of veterinary research, 62(7), pp.1068-1072.

Savas, I. and Raptopoulos, D., 2000. Incidence of gastro‐oesophageal reflux during anaesthesia, following two different fasting times in dogs. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 27(1), pp.54-62.

Savvas, I., Rallis, T. and Raptopoulos, D., 2009. The effect of pre-anaesthetic fasting time and type of food on gastric content volume and acidity in dogs. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 36(6), pp.539-546.

Savvas, I., Raptopoulos, D. and Rallis, T., 2016. A “light meal” three hours preoperatively decreases the incidence of gastro-esophageal reflux in dogs. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 52(6), pp.357-363.

Tsompanidou, P., Robben, J.H., Savvas, I., Anagnostou, T., Prassinos, N.N. and Kazakos, G.M., 2021. The Effect of the preoperative fasting regimen on the incidence of gastro-oesophageal reflux in 90 Dogs. Animals, 12(1), p.64.

Wilson, D.V., Evans, A.T. and Miller, R., 2005. Effects of preanesthetic administration of morphine on gastroesophageal reflux and regurgitation during anesthesia in dogs. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 66(3), pp.386-390.

Wilson, D.V., Evans, A.T. and Mauer, W.A., 2006. Influence of metoclopramide on gastroesophageal reflux in anesthetized dogs. American journal of veterinary research, 67(1), pp.26-31.

https://www.dailydogfoodrecipes.com/acid-reflux-dogschinese-medicine-perspective

Leave a reply to drramansahil Cancel reply